Climate Risk Meets Housing Affordability

Skriven av Author on .

When climate risk collides with housing affordability, the fault lines run through our economies, our communities and our futures. Climate change is no longer just a threat to coastlines but infact reshaping who can afford to live where, altering the flow of capital, and redrawing the map of opportunity.

From rising insurance premiums to shifting migration patterns, “safe haven” regions are becoming more desirable, more expensive, and more exclusive. This piece explores how we can build resilience that protects both people and portfolios.

In September 2023, New York City received more than 8.65 inches (21.97 cm) worth of rain in a single day, setting a new record for one day (Ley, 2023; NOAA, 2023). Streets turned into rivers, subway lines flooded, and basement apartments, often the most affordable housing, were destroyed. Similar to New York City, the City of Chicago experienced severe urban flooding in 2023 and 2024, submerging sections of the South and West Sides and prompting a substantial recovery investment, including $457 million for infrastructure and mitigation, $45 million for housing repairs, and $5 million for economic revitalization through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Community Development Block Grant–Disaster Recovery program. The plan focuses on three pillars: housing, infrastructure, mitigation, and economic revitalization. This includes repairing up to 1,600 homes, expanding drainage capacity on more than 233 city blocks, and revitalizing 50 storefronts in flood-affected corridors (U.S. HUD, 2025). While these cities are cultural and economic icons, their experiences highlight a global challenge: climate disasters destabilize housing markets, increase costs, and threaten the very economic mobility that draws people in.

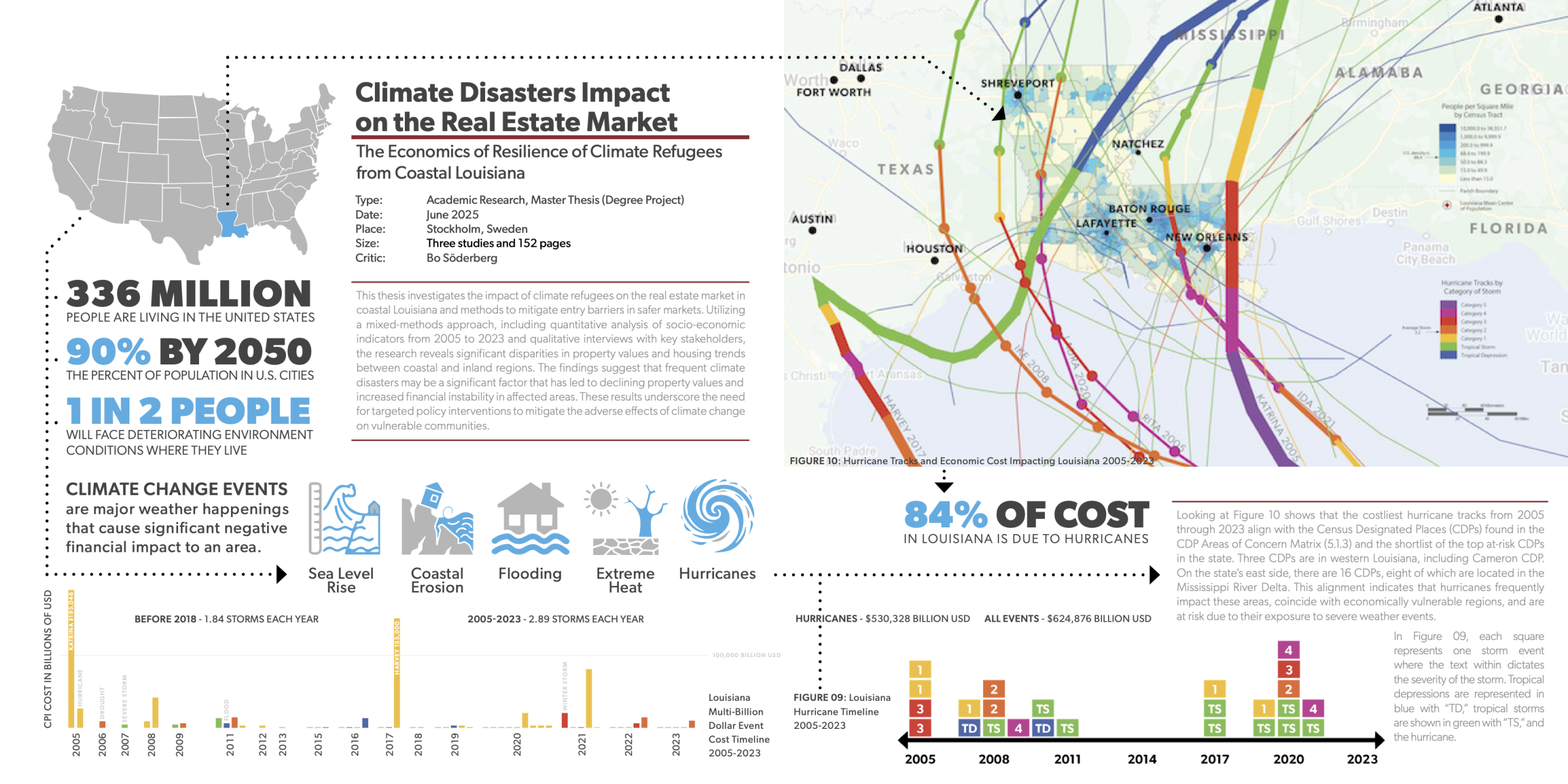

My name is Zachary Kunstman, and I am a pre-development consultant and real estate economist with a background in architecture and a focus on climate risk. Over the past several years, I have studied how climate disasters ripple through housing markets not just in the form of physical damage, but as shocks to affordability, credit, and long-term economic mobility (Kunstman, 2024).

Magdalena at Aputsiaq asked me to shed light on how climate risk and housing affordability intersect, and what this means for regions often seen as “safe havens” such as the American Midwest or the Nordic countries. These are the places that may attract more people in a warming world. Without thoughtful planning however, they risk becoming less accessible, less equitable, and less resilient.

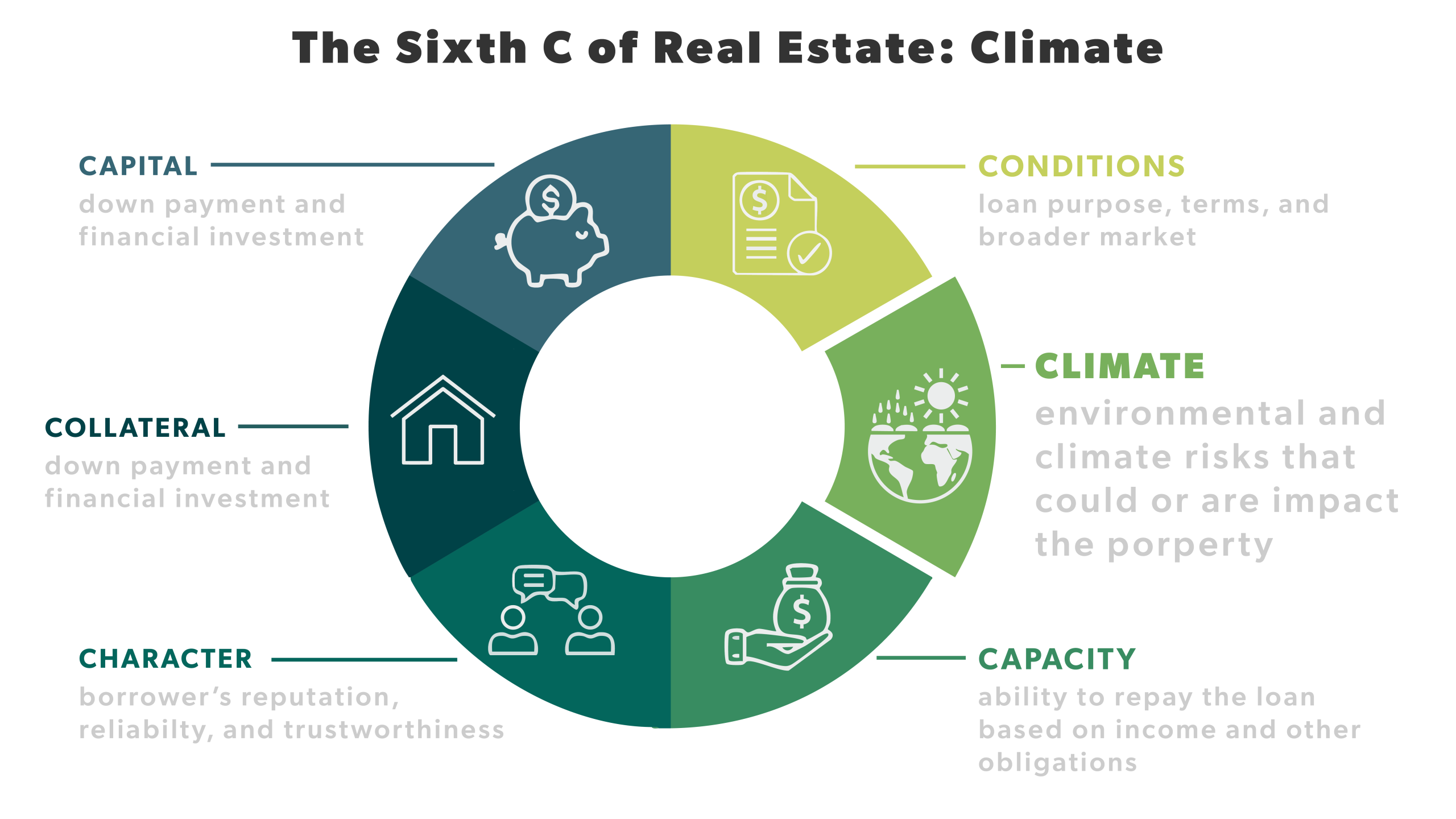

The Sixth C of Real Estate: Climate

For decades, mortgage underwriting has relied on the “five Cs” of credit: Character, Capacity, Capital, Collateral, and Conditions to assess borrowers and assets. In mortgage lending, Capacity refers to a borrower’s ability to make monthly payments, based on factors such as income amount, stability, type of income, and debt-to-income ratio. Collateral is the value of the home securing the loan, with lenders considering the property’s value, any debt already secured by it, and the remaining equity. Conditions cover broader market or economic factors, including the purpose of the loan, local economic health, and even environmental conditions — all of which can influence repayment risk (Wells Fargo, n.d.). Insurance costs, hazard exposure, and local climate trends already affect all three, but often indirectly.

Today, climate analysts argue for a sixth C: Climate. First Street has proposed making climate risk a formal “sixth C” of credit. Their analysis projects climate-related mortgage foreclosures will cost lenders $1.2 billion annually by 2025, rising to $5.4 billion by 2035 if risk continues to be underpriced. In severe years, nearly one-third of all foreclosure losses could be tied to climate hazards (First Street, 2025).

Embedding climate risk explicitly into underwriting could strengthen asset valuation and risk management. If insurers and lenders account for hazard data from flood maps to wildfire probability during loan origination, it can lead to more informed decisions. In that case, both the borrower and the lender have a clearer picture of the home’s long-term value. This isn’t just about protecting portfolios; it’s about making sure households don’t overextend themselves into unsustainable risk.

The Affordability Multiplier of Climate Risk

Climate disasters don’t just destroy property; they increase the cost of living in ways that ripple through regional economies for years. Insurance premiums are now a central affordability barrier. From 2018 to 2022, the U.S.

Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office (Treasury) found that homeowners in the 20% of Zone Improvement Plan (ZIP) Codes with the highest climate-related risk paid an additional average of $2,321 yearly, an annual premium 82% higher than those in the lowest-risk areas. Treasury also reported that households in hazard-prone regions are increasingly facing reduced coverage availability. (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2023). Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas (2025) shows that rising homeowners' insurance premiums strain household liquidity and increase the likelihood of mortgage delinquency, particularly for borrowers with higher debt-to-income ratios. As premiums climb, they raise total monthly housing costs, which can push some prospective buyers beyond qualifying thresholds for mortgage approval (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2025).

This mirrors findings from my research in coastal Louisiana, where insurance market instability, including coverage withdrawal and steep premium hikes, has accelerated population shifts and limited the economic mobility of households trying to relocate to safer areas (Kunstman, 2024; U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2023). For property owners on the front lines of risk, coverage primarily comes from two government-backed sources. The best known is the federal National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). The other option is that within thirty U.S. states, they operate their own Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plans. Both were born in the late 1960s and created in response to earlier insurance crises. The NFIP is under federal control, and state governments manage the FAIR Plans in partnership with the private market. But neither was built for an era of escalating climate risks. More than half a century later, as climate-related disasters intensify, both programs are straining under the weight of rising claims (Sedlar, 2023).

“insurer of last resort”

In Southern Florida, some homebuyers are being denied loans even when they meet the asking price because sharply higher homeowners' insurance premiums raise their total projected mortgage costs. Lenders factor these increased premiums into affordability calculations, and without adequate insurance coverage at a sustainable rate, mortgage approval may be delayed or denied (Crews Bank and Trust, 2025). In some coastal counties, private insurers have withdrawn entirely, leaving state-backed (NFIP) Citizens Property Insurance Corporation as the “insurer of last resort” (Office of Financial Research, 2024). The same dynamic is evident in Louisiana, where insurer exits after the 2020–2021 hurricane season forced thousands of households into the higher-cost Louisiana Citizens plan, which recently increased premiums by an average of sixty-three percent (Insurance Information Institute, 2023; First Street 2023).

The Dallas Fed’s analysis found that rising homeowners’ insurance premiums are associated with a higher probability of mortgage delinquency and with increased prepayments, as some households sell or refinance, which reflects patterns consistent with relocation to more affordable areas (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2025). First Street warns that surging insurance costs in Louisiana, projected to climb another 17.4% annually, could slash property values by nearly half over the next three decades (First Street, 2023). This aligns with my thesis findings in Louisiana:

insurance cost inflation is one of the most immediate triggers of forced migration from high-risk markets (Kunstman, 2024).

Safe Havens: Promise and Pressure

When people leave high-risk areas, they often seek “climate safe havens,” or areas that are less suseptible to future disasters. In the U.S., this can mean parts of the Midwest such as Fort Wayne, Indiana; Appleton, Wisconsin; and Cleveland, Ohio, where fewer than ten percent of homes face severe climate hazards (Investopedia, 2024). In Europe, the Nordic countries are often regarded as relatively secure due to their strong governance systems, advanced infrastructure, and generally lower exposure to specific climate hazards such as hurricanes and large-scale wildfires. While flooding and other climate impacts remain concerns, the region’s high adaptive capacity and proactive planning contribute to its resilience (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023; European Environment Agency, 2024). But safety attracts demand, and demand can push prices beyond reach for those from these safe havens and those seeking refuge. Safe havens themselves face supply constraints. As in-migration drives demand, prices rise, limiting access for the very populations most impacted by climate change (The Guardian, 2024). An influx of new residents can spur development that overlooks quality of life, ignores the needs of future residents, and ultimately worsens the climate crisis. Without targeted housing policies, the “safe” markets risk becoming exclusive enclaves. Understanding who is most vulnerable to disasters is essential for planners, government agencies, and community leaders to prepare effectively and respond when a crisis strikes.

Economic Mobility and Generational Wealth

Repeated disasters and insurance instability can erase generations of accumulated wealth, especially in communities with deep historical, cultural, or tribal ties to the land. In Louisiana, for example, some tribal communities have turned down relocation offers, even with government assistance, because the land holds cultural significance that can’t be replicated elsewhere (Loginova & Cassel, 2022).

My master’s thesis found that the timing of a household’s exit from a high-risk area is the single most crucial factor in preserving economic mobility (Kunstman, 2024). Economic mobility is a fundamental concept that refers to the ability of households or individuals to enhance their economic status over time (Institute for Research on Poverty, 2020). Early movers (the first quartile) can often sell into strong demand and retain equity for a purchase in a safe haven. By the second quartile, demand for the high-risk market has softened, reducing sale prices. Once more than half of the market has left, service closures such as schools, grocery stores, and fire departments can trigger near-total market failure. In the last quartile, there may be virtually no resale value, leaving households unable to finance a move. The ability to move is a form of resilience (Kunstman, 2024; Institute for Research on Poverty, 2020).

These factors create a dual challenge: those who stay face repeated disaster losses, eroding home equity and savings; those who delay moving until market collapse have diminished buying power in safer regions. In both cases, generational wealth and economic mobility are at risk.

Building Resilient and Inclusive Markets

A resilient housing market must be both climate-prepared and accessible. This means embedding climate considerations into every stage of real estate finance, planning, and policy. The European Environment Agency (2025) stresses the importance of transparent information on climate hazards for all stakeholders; in the real estate sector, this could include making climate risk disclosure standard practice at the point of sale and mortgage origination so buyers and lenders have a clearer picture of hazard exposure and potential insurance costs (European Environment Agency, 2025). Second, lenders need to integrate climate data into underwriting, stress-testing borrowers for possible premium increases over the life of the loan, a lesson reinforced by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas (2025), which found that higher insurance costs raise delinquency risk (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2025).

If we price risk honestly, fund adaptation smartly, and protect mobility for households, not just portfolios, people can keep thriving in the places they love.

To strengthen resilience, the property insurance systems must align more closely with climate realities. Affordable coverage in high-risk areas may help in the short term, but it can also obscure the severity of climate threats and give homeowners a false sense of security. Embedding long-term climate considerations into insurance policy design is essential. This type of reform will help protect property and livelihoods today while ensuring that future housing markets remain safe, stable, and sustainable (Lustgarten, 2020).

Equally important is investing in adaptation infrastructure in high-risk regions, from upgraded stormwater systems to building retrofits, to slow displacement and stabilize local insurance markets (OECD, 2024; GIZ, 2022). For “safe haven” areas, proactive housing policy is essential to prevent exclusion — mixed-income housing development, mobility-focused assistanceprograms, and affordability safeguards can ensure that in-migration doesn’t push out vulnerable residents (The Guardian, 2024; Kunstman, 2024). Finally, improving transparency in hazard and insurance data will help lenders and buyers avoid “hidden cliffs” where eligibility suddenly disappears, as seen when real estate assets in Florida became ineligible for conventional mortgages due to reserve or insurance shortfalls (OECD, 2024).

Key actions include:

• Standardize climate risk disclosure at point of sale and loan origination

• Integrate climate into underwriting and stress-test for insurance cost increases

• Invest in adaptation infrastructure in both high-risk and receiving areas

• Support affordability in safe havens through housing policy and assistance

• Improve hazard and insurance data transparency for lenders, insurers and buyers

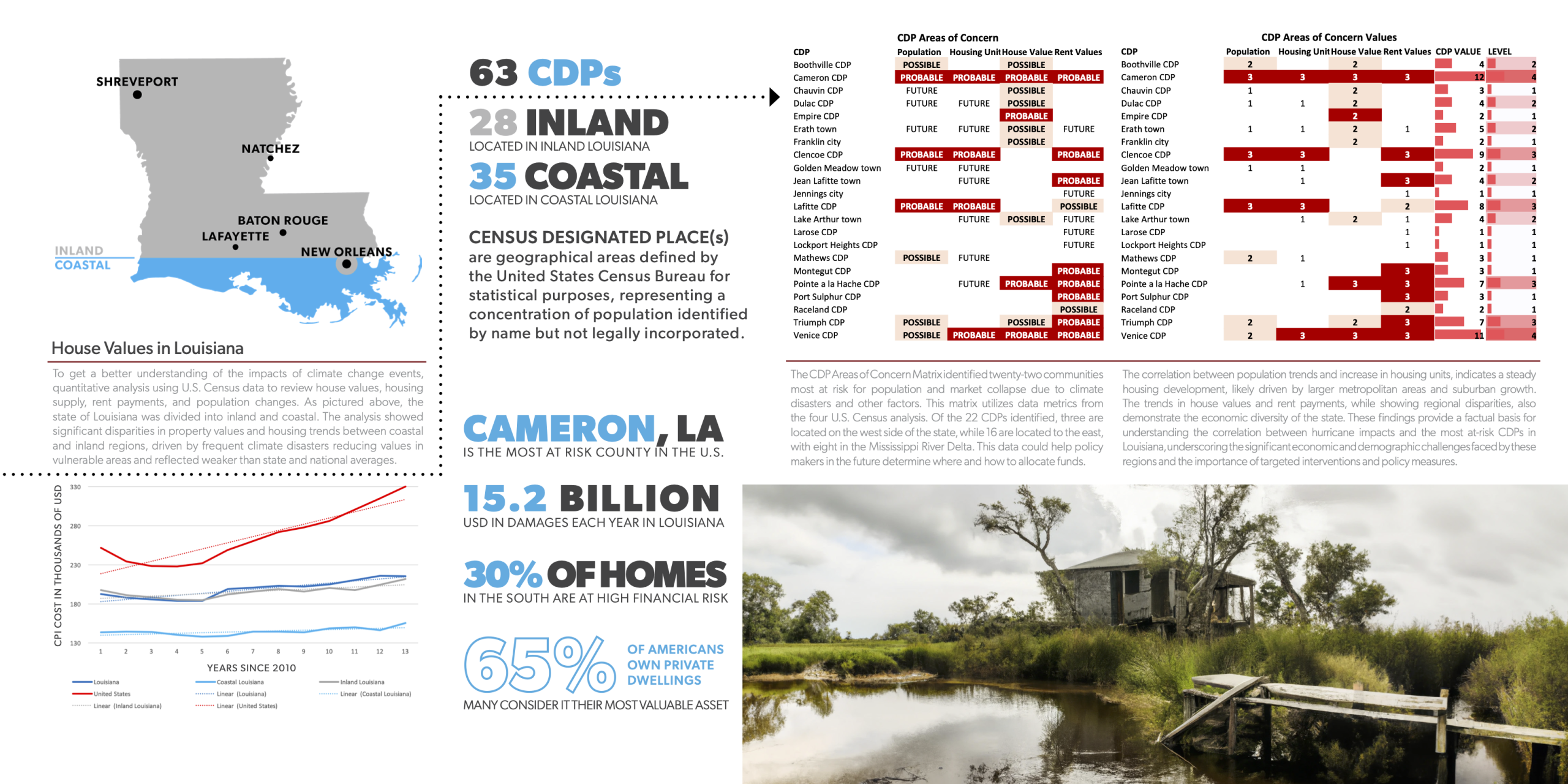

From my research, it shows that climate refugees often struggle to enter safer housing markets due to limited economic mobility, with record rent and home price increases in safer regions and stagnant values in those they leave behind (USCB, 2010–2022). In Louisiana, the gap between local and national housing costs can trap residents in place, a challenge made more pressing given that over 65% of Americans own homes they consider their most valuable asset (Hill, 2023).

As climate events intensify, these divides could further limit relocation opportunities, hinder generational wealth transfer, and demand long-term policies that ensure distributive justice across generations (Gibbons, 2014).

In Conclusion

From flooded basements in New York City to rising premiums in Miami and in-migration pressures in the Nordics, the connection is clear: finance is now the front line of climate resilience. When risk shows up first in insurance and credit markets, it determines who can buy, who can sell, and who can move.

The evidence is clear — the Sixth C of credit is already here, even if many underwriting models have yet to acknowledge it. The affordability multiplier is squeezing households from both ends, as insurance inflation raises borrowing costs and asset values in high-risk markets stagnate or fall (First Street, 2025). Safe havens, while offering refuge, face their own pressures as demand outpaces supply, threatening to recreate the very inequities they are meant to solve. And as my research shows, timing matters: early movers preserve mobility; late movers can find themselves locked in place, watching opportunity slip away.The Nordic countries are in a particularly strong position to help address these challenges. With some of the highest renewable energy adoption rates in the world, a tradition of people-first urban development, and social housing systems that aim for inclusivity, the region offers valuable lessons for building markets that are both resilient and equitable (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023). If these approaches are adapted to prepare for climate migration and integrated into financial planning, the Nordics could not only safeguard their housing markets but also serve as a model globally.

I remain optimistic. We have the tools: transparent climate risk data, adaptable underwriting, targeted housing policies, and strategic infrastructure investments that can shape markets to be both resilient and inclusive. But we must act early and decisively. This is not just about protecting portfolios; it is about ensuring that families, communities, and cultures can continue to thrive where they choose to live.

If we price risk honestly, fund adaptation smartly, and protect mobility for households, not just portfolios, people can keep thriving in the places they love.

References

Crews Bank and Trust. (2025, February 26). How Florida’s hurricane season impacts home mortgages. https://www.crews.bank/blog/buying-a-home/how-floridas-hurricane-season-impacts-home-mortgages

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). (2022). Ecosystem-based adaptation and insurance: Success, challenges and lessons learned. GIZ. https://

www.adaptationcommunity.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/EbA-and-Insurance_Success-Challenges-Lessons-Learned.pdf

European Environment Agency. (2024, March 18). Leave no one behind: Social sustainability in Climate change adaptation. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/newsroom/news/leave-no-one-behind

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. (2025). Insurance premiums and mortgage performance (Working Paper No. 2505). https://www.dallasfed.org/-/media/documents/research/papers/2025/wp2505.pdf

First Street Foundation. (2023). What will climate risk cost you? https://firststreet.org/research-library/what-will-climate-risk-cost-you

First Street Foundation. (2025). Climate as the Sixth “C” of Credit. https://firststreet.org/research-library/climate-the-sixth-c-of-credit

Gibbons, E. D. (2014). Climate change, children’s rights, and the pursuit of intergenerational climate justice. Health and Human Rights, 16(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/healhumarigh.16.1.19

Hill, A. C. (2023). Climate change and U.S. property insurance: A stormy mix. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/article/climate-change-and-us-property-insurance-stormy-mix

Institute for Research on Poverty. (2020). Conceptualizing mobility. https://www.irp.wisc.edu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Economic-Mobility-Memo-1-Definitions-and-Trends-April-2020.pdf

Investopedia. (2024, August 12). Midwest cities with minimal climate risks. https://www.investopedia.com/midwest-cities-with-minimal-climate-risks-8782436

Kunstman, Z. (2024). Climate disasters’ impact on the real estate market: The economics ofresilience of climate refugees from coastal Louisiana (Master’s thesis, KTH Royal Institute ofTechnology). KTH Royal Institute of Technology. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1874537

Loginova, O., & Cassel, Z. (2022, August 17). Leaving the island: The messy, contentious reality of climate relocation. The Center for Public Integrity. https://publicintegrity.org/environment/harms-way/leaving-isle-de-jean-charles-climate-relocation/

Lustgarten, A. (2020, September 15). How climate migration will reshape America. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/09/15/magazine/climate-crisis-migration-america.html?searchResultPosition=2

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2023, October 13). U.S. just had its 7th-warmest September on record. NOAA. https://www.noaa.gov/news/us-just-had-its-7th-warmest-september-on-recordNordic Council of Ministers. (2023). Policy landscape in the five Nordic countries. In Nordic climate change adaptation: Policy landscape and key initiatives (pp. 53–67). Nordic Council of Ministers. https://pub.norden.org/temanord2023-510/7-policy-landscape-in-the-five-nordic-countries.html

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024). Climate resilient infrastructure:

Policy perspectives. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/a74a45b0-en

Sedlar, M. (2023). Climate change and the future of catastrophe insurance programs. Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net

The Guardian. (2024, September 22). Americans move to the Midwest as climate crisis bites.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/sep/22/climate-crisis-americans-move-midwest

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2025). City of Chicago CDBG-DR program overview. https://www.chicago.gov/cdbgdr

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2023, October 19). Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office launches data collection to assess climate-related financial risks to U.S. homeowners insurance market [Press release]. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2791

United States 2Bureau. (2010-2023). Selected housing characteristics (American Community Survey [ACS], 5-year estimates data profiles, Table DP04 [CDP]). U.S. Census Bureau.

Wells Fargo. (n.d.). Five Cs of credit: What lenders look for. https://www.wellsfargo.com/financial-education/credit-management/five-c/

Ley, A. (2023, September 29). Rain wreaks havoc on New York’s mass transit system. The NewYork Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/29/nyregion/nyc-flood-mta-subway.html

Tagged

You might also like

-

Sociodukter Gästblogg av Axel Strandberg

- Skriven av Author

- Publicerad

-

När klimatrisken möter bostadsmarknaden: Vilka har råd att bo säkert?

- Skriven av Magdalena

- Publicerad